With the release of Django 4.0, there was a minor change to how Django handles CSRF protections: the Origin header is now checked, if present. Specifically, the URL scheme is now checked.

Now, this seems like an innocuous change, something that shouldn’t affect many users. However, this change would break Django 4.0 deployments to Cloud Run using our tutorial.

But not deployments to App Engine.

What follows is one engineer’s story (hi!) into the depths of managed services, web server gateway interfaces, and magic strings.

Managed hosting manages your hosting, turns out

When you use managed hosting, you delegate control of part of your deployments to that system. You don’t have to worry about parts of your stack, and you get to take advantage of the platform SLAs. But, by design, that means you don’t have access to parts of the stack.

For serverless hosting with Cloud Run and App Engine, that means you let Google control the web server onwards. You provide a bundle of code, in a container or zip file respectively, and the command to make the thing go. Google Cloud then handles the servers that data is stored on, power and networking to those servers, server maintenance, all that stuff, all the way down to the important parts closer to your application: the domain you use to access your deployed site, including the security behind its HTTPS address, and the proxy that directs that traffic to your application.

Cloud Run and App Engine both provide a HTTPS URL for your application, meaning that there is bidirectional encryption of data going between your users and your server, with TLS termination handled for you. Additionally, as per the Container Runtime Contract, Cloud Run will proxy requests to your container from the incoming HTTPS to HTTP for you. This will be important later.

An interface by any other name would smell as smokey

While you don’t have control over which web server your managed hosting uses, you still need to have an application that responds correctly. For Python developers, using a WSGI server handles all this for you. Defined in PEP-333 and later revised in PEP-3333, a Python Web Server Gateway Interface (WSGI) (also pronounced whiskey, or WIZ-ghee) is supported by many frameworks, meaning you can use any WSGI server you wish with your web framework of choice (in this case, Django).

WSGI adopts some conventions from the RFC3875 Common Gateway Interface (CGI) standard, which is mentioned in the WSGI standard itself. This will become important later.

Request goes in, response goes out

An HTTP web application will have responses to various methods: there are ‘safe’ methods—those that don’t affect the website data, and are effectively read-only. The real problems come in when you start accepting requests that can manipulate data. These methods have side effects, but also contain user data. User data is one of the most dangerous things in web development: you cannot trust it. Ever.

Many web frameworks help developers by providing protections against common issues with user data, including but not limited to SQL injection mitigations and Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) protections.

While HTTPS secures the contents of the request, CSRF attacks target the header information, allowing for the credentials from an authenticated user to be used without their authorization. This isn’t the same as clickjacking, where a user would have to interact with a website; CSRF doesn’t require any interaction at all, and exploits the trust that a web application has in an authenticated user.

What was that explosion noise?

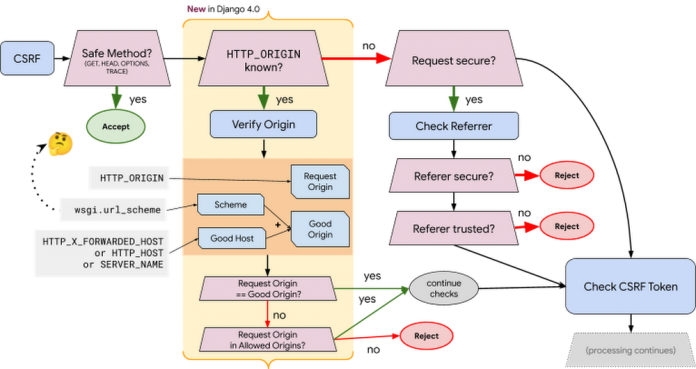

Django has included CSRF protections since before its 1.0 release, but previously the value was expected to only be a host name. Django 4.0 introduced a change where you have to additionally provide the scheme. For instance: a value that was previously now “mysite.org” is now “https://mysite.org”.

Configuring trusted origins for CSRF, is an optional setting, much like ALLOWED_HOSTS. ALLOWED_HOSTS is a setting that allows you to define what host the Django application should be running (though you can choose to allow all hosts). For all incoming requests, Django gets the host from the HTTP_HOST header (from the CGI standard), or SERVER_NAME (from the WSGI standard). If this host is not in the ALLOWED_HOSTS, it will error.

CSRF protections are more complicated: if the method is ‘unsafe’, Django verifies the request origin matches the ‘good’ origin. Django gets the request scheme as provided by the WSGI server, and concatenates the host name from one of the various HTTP headers.

Who defines the scheming around here?

Knowing the scheme is an important part of CSRF processing. But being able to determine the scheme in a trusted and verified method is tricky.

CGI specifically does not define this, but does warn that the scheme https is not the same as port 443, and offers that scripts use other metadata to determine the scheme. WSGI defines an optional environment variable called url_scheme, but does not define how to determine it.

At the time of writing, common Python WSGI servers use the following methods to determine the URL scheme based on the information that it receives from the web server:

uwsgi directly passes on the X-Forwarded-Proto header, which returns through Cloud Run as https.

waitress does not handle TLS, and so will always return http (unless you set –url-scheme https when calling waitress-serve.

gunicorn will check if there are any certificates defined, but also allows setting forwarding IPs, which by default includes 127.0.0.1.

Django checks the wsgi.url_scheme value, which if you use gunicorn (as many of our Python samples do) returns https in App Engine because App Engine’s web server runs as 127.0.0.1, but returns http in Cloud Run because Cloud Run uses a different private IP.

So everything breaks on Cloud Run. 😢

The most correct answer

For Django applications, the correct solution is to configure the CSRF_TRUSTED_ORIGINS and ALLOWED_HOSTS variables in your settings.py file. It is my opinion that this is the safest solution, though it does require an extra step when first deploying your site.

The Django on Google Cloud tutorials have been updated to accept an environment variable of the service URL, and convert that value to the format each of the settings require. To get the service URL, run the follow command:

Cloud Run: gcloud run services describe SERVICE –format “value(status.url)”

App Engine: gcloud app describe –format “value(defaultHostname)”

Ah I see you have a machine that goes, “ding!”

As applications get more complex, there are increasingly complex problems you have to consider, especially if you’re storing and allowing manipulation of data. By ensuring that you provide enough information to your application’s underlying logic, you can take advantage of all the previous work, standards, and best practices to ensure you don’t have to worry as much.

Cloud BlogRead More